Small tales, generally of love

On John and Paul: A Love Story in Songs, and the novelistic turn in non-fiction

“A small tale, generally of love.” That’s how Dr Johnson, in his dictionary, defined a novel — and in doing so, gifted generations of writers with an epigraph for the ages. It’s been quoted so often I’ve never felt the need to confirm it myself, relying instead on the honesty and diligence of J.L. Carr (A Month in the Country) and Julian Barnes (The Only Story) to vouch for its truth.

If I had to name, right now, the book most deserving of that epitaph — not just in recent memory, but more than most books I can think of — I wouldn’t, however, choose a novel at all. I’d choose a work of non-fiction instead: Ian Leslie’s John and Paul: A Love Story in Songs.

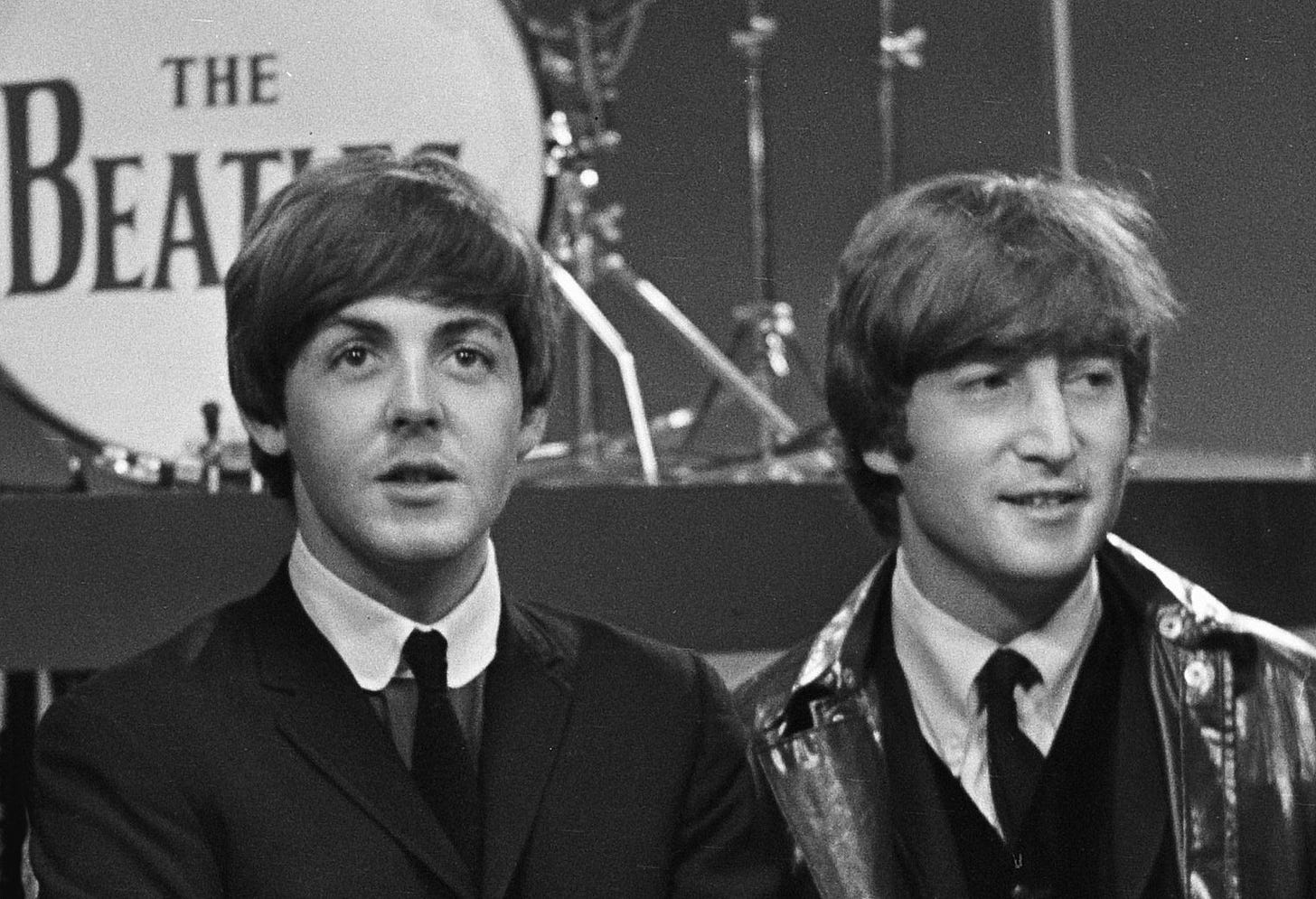

Leslie’s book, published earlier this year, sets itself a deceptively simple task: to tell the story of the relationship between John Lennon and Paul McCartney — two twin-track geniuses who emerged, as he puts it well, with “wild improbability,” from suburban 1950s Liverpool to form one of the greatest creative collaborations of all time.

Each chapter is built around a single song, which serves as an emotional and narrative hinge, moving the story one beat further along a path that, for most readers, will be well-trodden: the first meeting at a church fête in Woolton; the chaotic apprenticeship in Hamburg; the explosion of Beatlemania; and, inevitably, the fall.

There’s no newly unearthed diary, no rediscovered footage (unlike Peter Jackson’s Get Back, which features heavily in the second half of the book). None of the information is new — no lost Vermeer in the attic here. And that, in a way, is the point. Instead of focussing on how things happened, Leslie devotes himself almost exclusively to why.

What emerges is less an arid reference book of facts, more a psychological study of an intense friendship — the kind we usually encounter in fiction: Hollinghurst’s Nick and Toby; O’Brien’s Aubrey and Maturin; Ferrante’s Lenu and Lila. Indeed, it’s this last comparison that Deborah Levy returns to repeatedly in her New Statesman review; several paragraphs in, she’s already musing about which Beatle is which.

It’s precisely this novelistic quality, I think, that makes Leslie’s book so addictive — and also, as I’ll return to later, a useful model for what non-fiction should aim to do in a world where AI can now deliver facts faster, cheaper, and more neatly than any human ever could.

That might sound lofty, but it comes from a very simple truth: people just can’t seem to put it down. It’s a recurring theme in the reviews and interviews surrounding John and Paul’s publication. Tyler Cowen read it in a single sitting (‘I started it, and I didn’t really get up till I finished it’), Ed West did it in ‘a day and a morning.’

As someone who rarely reads non-fiction — and for whom, frankly, the Beatles’ greatest impact on my life has been forcing me to wait an extra five minutes at the Abbey Road crossing on the way to Swiss Cottage soft play centre — I was not expecting similar results. To my surprise, I found myself reading it in a single, compulsive afternoon.

Leslie’s role in the story is intriguing: less an objective chronicler than a gentle guide. The facts he relays are essentially the same you’d glean from any Wikipedia page about the pair: they met when Paul was fifteen and John sixteen; they all crammed into a single room in Hamburg; both struggled profoundly with their identities after the Beatles broke up.

His skill, instead, is in prompting us to remember things we really should notice more deeply, yet rarely do: the fact that when you’re fifteen, someone almost two years older than you seems a different species entirely; the raw squalor and utter lack of boundaries inevitably created when teenage boys share close quarters for extended periods; and the stark reality that, as the world’s first true pop megastars, they were also humanity’s earliest experiment in navigating what comes next — how to manage breakups, forge solo identities, and inhabit the long shadow of extraordinary fame.

In doing so, he helps us get a little closer to solving the thing I’ve always struggled to understand about Lennon and McCartney: how, from such inauspicious beginnings, they came to be so great. Was it contingency — the great cosmic monkey at the typewriter striking gold for a few sentences — or something more inevitable? A brief historical window when class mobility, mass media, and youth culture all aligned just long enough for lightning to strike.

Leslie’s answer, I think, is that it's better to think about John and Paul as two facets of a single joint personality. The kind that often forms in couples — usually romantic — who meet young and stay close: growing through their twenties in such mutual proximity (Leslie writes of the “shared ownership of each other’s talent”) that, by the end, it’s hard to tell where one stops and the other begins. “It's like you and me are lovers,” John says to Paul at one point.

It’s not just the music either. When John left Cynthia and young Julian for Yoko Ono in 1968, it was Paul who jumped in the car and drove to Weybridge to check on them, workshopping Hey Jude on the way there and back. And in 1974, when John and Yoko’s marriage briefly fell apart, Yoko once again turned to Paul — asking him to tell John that she wanted to reconcile.

It’s a strange kind of relationship when you’re responsible for creating each other. The upside is the depth of alignment, the kind of unspoken shorthand you can see flickering between John and Paul in real time during the Get Back sessions. The downside is that certain habits — jealousies, paranoia and needling — freeze at the age you met and sometimes never thaw.

These kinds of relationships don’t really get written about in novels anymore. Which is why it falls to Leslie to fill in the gap with his own version. In doing so, he doesn’t just help us explain the why of the Beatles, but also, I think, to answer a larger question: in a world of AI, what’s left for a non-fiction writer to do?

The first line of the Wikipedia entry for non-fiction reads: “non-fiction (or nonfiction) is any document or media content that attempts, in good faith, to convey information only about the real world, rather than being grounded in imagination.”

That’s a fair summary of the role non-fiction has traditionally played in the literary world: the purveyor of facts. Style and narrative matter, of course, but ultimately, we go to these books for cold, hard information. The trouble is, that role is now almost obsolete. If I want to find something out, I can open GPT or Claude, ask a question, and get a faster, cheaper, often more accurate response than any book could deliver.

For the unimaginative, the future seems obvious: farewell to the non-fiction book. But John and Paul reminds us there’s much more to it than that, and that survival here is not as difficult as it first looks. The way forward lies not in retreating from fiction, but in adopting its sensibility: tone, texture, character, pacing — leaning towards, not away from, the novelistic sensibility.

In the same way a novel keeps us reading — layering one pleasing sentence after another — so too must a book like this. John is not simply a conflicted husband and father, but a man capable of “loving them, but not wanting to be tied to them.” Strawberry Fields and Penny Lane are not competing tracks, but songs “radically different, but umbilically connected.” The country they came from is not just old, but one belonging to a “long-gone era of top hats and dirty chimneys.”

Not everything is theory and feeling, either. There’s Paul McCartney, post-Beatles, remixing Mary Had a Little Lamb and touring the pubs and inns of England. Lennon, determined to sail a 43-foot sloop from New York to Bermuda, despite no clear qualifications. And the surreal scheme to buy a Greek island—foiled not just by the fantastical stupidity of the plan itself, but by Britain’s post-war exchange controls, requiring an intervention from James Callaghan.

It helps that the structure works. In an interview, Leslie mentioned first attempting a thematic approach, but found himself drawn back to the pull of a chronological story. He was right to allow a good amount of personal sensibility into play: enough to shape the story, but never so much that it tips into memoir or solipsism.

This matters because, in the world I’ve described above, the rare thing — the thing still worth paying for — is voice. Not expertise in the traditional sense, but sensibility: the ability to make you feel something, notice something, linger a little longer than you otherwise would. John and Paul isn’t just a collection of facts about the Beatles; it’s a carefully arranged experience of tone, attention, and perspective.

This isn’t a book you could reduce to a summary or a Twitter thread, as you might with, say, Atomic Habits. To do so would miss the point entirely — like reading a synopsis of a novel and thinking you know what it feels like when a character you’ve rooted for over 600 pages drowns five pages before the end.

This is less radical than it might first sound. Good non-fiction has always worked this way. Think of Blake on Disraeli, Uglow on Hogarth, Lee on Woolf; the narrative thrust of Dominic Sandbrook’s histories of the 1980s; Ben Macintyre’s tales of spooky derring-do. Or think of the television essayists of the 1970s: Robert Hughes in a red convertible, slagging off Le Corbusier; John Berger listening as his female friends discuss the male gaze, cigarette in hand. The subtitle of Civilisation, after all, is ‘a personal view.’

The difference now is that this kind of sensibility isn’t a bonus — it’s the price of entry.

The same cuts the other way. One reason Deborah Levy draws a line from John and Paul to Ferrante is that she sees little distinction between them: her own trilogy of memoirs often reads more like fiction than diary. From Geoff Dyer to Maggie Nelson to Miranda July, the boundaries have been dissolving for a while. Rather than seeing this shift as a sudden break triggered by AI, it’s more accurate to view it as the solidification of a much longer trend — fiction becoming more like non-fiction; non-fiction becoming more like fiction.

John and Paul, unexpectedly but satisfyingly, fits squarely into this tradition. The result is not only the kind of writing that belongs in a world where no reader is willing to sift through dense, impenetrable prose just to find one nugget of gold, but also a glimpse of where non-fiction might be headed: part biography; part criticism; and part story of two men who, for a time, shared one mind.

Or, as Dr Johnson might have put it: a small tale, generally of love.